Today’s post will provide an overview look at Alzheimer’s Disease. As I’ve stated before, Alzheimer’s Disease is a specific type of brain deterioration disease (dementia) that differs from other dementias.

While Alzheimer’s Disease is a type of dementia, not all dementias are Alzheimer’s Disease. “Alzheimer’s Disease” has become the catch-phrase for all neurological degeneration among the general population and that imprecision leads to a lack of understanding of the complexities of these diseases, especially when several types of dementia are present concurrently.

Dementias affect specific areas of the internal structure of the brain and are caused by specific abnormal occurrences within those areas. We’ve looked at vascular (multi-infarct) dementia, which is a result of small vessel ischemia within the blood vessels in the brain, and Lewy Body dementia, which occurs when abnormal proteins are deposited in the cortex of the brain.

Alzheimer’s Disease affects the whole brain, essentially eroding and diminishing, through the resulting atrophy, the whole structure of the brain. The two crucial components in Alzheimer’s Disease are the overabundant presence of plaques (beta-amyloid protein deposit fragments that accumulate in the spaces between neurons) and tangles (twisted fibers of disintegrating tau proteins that accumulate within neurons). Watch this short video to see how these plaques and tangles form and how they lead to neuron death.

Alzheimer’s Disease affects the whole brain, essentially eroding and diminishing, through the resulting atrophy, the whole structure of the brain. The two crucial components in Alzheimer’s Disease are the overabundant presence of plaques (beta-amyloid protein deposit fragments that accumulate in the spaces between neurons) and tangles (twisted fibers of disintegrating tau proteins that accumulate within neurons). Watch this short video to see how these plaques and tangles form and how they lead to neuron death.

While plaques and tangles, which lead to neuron death (the nerve cells get deprived of what they need to survive and be healthy), are part of the aging process, in our loved ones with Alzheimer’s Disease, there are so many of them that the brain slowly dies from the inside out.

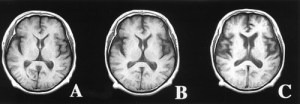

It is clear from the picture above exactly why Alzheimer’s Disease is a systemic disease, because all areas of the brain are eventually impacted.

However, as Alzheimer’s Disease begins, the first area of the brain affected is the temporal lobe, which is, in part, responsible for long and short-term memory, and persistent short-term memory loss is usually one of the first symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease to appear.

for long and short-term memory, and persistent short-term memory loss is usually one of the first symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease to appear.

The second area of the brain to be affected is generally the frontal lobe, which handles information processing and decision-making. The last part of the brain to be affected is usually the parietal lobe, which is the area of the brain responsible for language and speech.

Alzheimer’s Disease has distinct stages in which symptoms materialize. The stages are (this lists the three main stages, but there is also a more comprehensive seven-stage breakdown, known as the Global Deterioration Scale or the Reisberg Scale):

- Stage 1 – Mild – Recurring short-term memory loss, especially of recent conversations and events. Repetitive questions and some trouble with expressing and understanding language. Possible mild coordination problems with writing and using objects. May have mood swings. Need reminders for some daily activities, and may begin have difficulty driving.

- Stage 2 – Moderate/Middle – Problems are evident. Continual memory loss, which may include forgetting personal history and the inability to recognize friends and family. Rambling speech. Unusual reasoning. More confusion about current events, time, and place. Tends to get lost in familiar settings. Experiences sleep issues (including sundowning). More pervasive changes in mood and behavior, especially when experiencing stress and change. May experience delusions, aggression, and uninhibited behavior. Mobility and coordination may be affected. Need set structure, reminders, and assistance with daily living.

- Stage 3 – Severe/Late – Confused about past and present. Loses all ability to remember, communicate, or process information. Generally incapacitated with severe to total loss of verbal skills. Unable to care for self. Often features urinary and bowel incontinence. Can exhibit extreme mood disturbances, extreme behavior, and delirium. Problems with swallowing occur in this stage as well.

It’s important to remember that not all our loved ones with Alzheimer’s Disease – especially if there are other dementias present – will go through every aspect of each stage nor through all the stages before they die. That’s one of the real difficulties with “mixed-dementia” diagnoses, as these are called, because it’s difficult to tell which brain disease is causing which problems and that makes them more difficult to manage symptom-wise.

The medications generally prescribed for Alzheimer’s Disease are Aricept (mild to moderate stages), Namenda (moderate stage), and Excelon (mild to moderate). All three of these medications are cognitive enhancers. It’s not unusual to have more than one of these medications prescribed at a time.

I will talk specifically about sleep disturbances in dementias and Alzheimer’s Disease, including sundowning, in another post, but I will caution all caregivers to stay away from both non-prescription sleep medications like Tylenol PM, Advil PM, and ZZZQuil and prescription sleep medications like Lunesta and Ambien (all of these can actually make the symptoms worse and definitely make injury and/or death from a fall more likely).

Melatonin is naturally-occurring sleep hormone in humans. As people age, there is less melatonin produced. That’s why, in general, most older people who have never had sleep disorders eventually and gradually sleep less than their younger counterparts. However, the brain damage that dementias and Alzheimer’s Disease cause exacerbates this lack of melatonin.

So, it’s worth it to try a therapeutic dose (up to 20 mg per night is considered to be safe) of Melatonin. It is available over-the-counter at both brick-and-mortar and online drug stores.

Start with a 3 mg dose and add slowly. With my mom, a 5 mg dose provided enough for her to sleep as best as she could through the night. Do not overdose because this will disrupt the circadian rhythm further by producing late sleeping and grogginess during the day.

Usually our loved ones with dementia and/or Alzheimer’s Disease, even though these diseases are fatal (when the brain’s dead, you’re dead), don’t die from them specifically.

They die either from a concurrent health problem (in my mom’s case, it was congestive heart failure which lead to a major heart attack, a minimal recovery, and then her death twelve days later) or from complications that arise from the brain degeneration caused by the dementias and/or Alzheimer’s Disease.

The two most common causes of death in Alzheimer’s Disease are pneumonia (the brain controls swallowing, and once that becomes compromised, aspiration of food into the lungs is likely and leads to an infection) and fatal trauma to the head from falls.