The answer is “probably.”

The answer is “probably.”

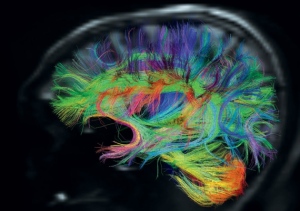

There have been several studies in the last two years on the effects – positive and negative – of sleep on the brain. They all agree on one point: to function optimally, the brain requires quality sleep and enough of it.

They also agree on another point: the way our modern society is structured, the majority of us are not getting enough sleep, and the little sleep we are getting is not quality sleep.

The fact that poor sleep and future dementia are linked is not new.

A sleep disorder known as REM sleep behavior disorder is a key characteristic of Lewy Body dementia, but the sleep disorder is often present decades before symptoms of Lewy Body dementia emerge.

In a study published in the The Journal of the American Medical Association in 2011, researchers showed a strong link between sleep apnea (sleep-disordered breathing) and dementia.

However, new research is now showing that even those of us without these two sleep disorders are getting less sleep and the sleep we do get is not quality sleep. New neurological research is showing us how important enough sleep and good sleep is for our present and future neurological help.

The body has a natural circadian rhythm designed to promote and facilitate sleep as daylight turns into evening and then night and to promote and facilitate wakefulness as night turns into day.

The body has a natural circadian rhythm designed to promote and facilitate sleep as daylight turns into evening and then night and to promote and facilitate wakefulness as night turns into day.

Until the Industrial Revolution, which actually consists of two iterations (one in the late 18th century and the second, which was the more profound of the two, in the mid-19th century, the human race generally slept and awakened based on the body’s natural circadian rhythm.

After the second iteration of the Industrial Revolution, when crude ways to keep the lights on 24 hours a day, 7 days a week emerged, all that changed. Initially, the only segment of the population that it affected were those who were employed in factories, mines, and foundries.

As textile factories, ore and mineral mines, and metal foundries remade the work day into two 11-hour shifts – generally, 7 am – 6 pm and 7 pm – 6 am – the second shift of workers were forced to ignore and work against their natural circadian rhythms to fuel the manufacturing boom, which was bolstered by a greater demand for manufactured goods throughout all strata of the population.

As textile factories, ore and mineral mines, and metal foundries remade the work day into two 11-hour shifts – generally, 7 am – 6 pm and 7 pm – 6 am – the second shift of workers were forced to ignore and work against their natural circadian rhythms to fuel the manufacturing boom, which was bolstered by a greater demand for manufactured goods throughout all strata of the population.

Although there was less concern about the workers – health, quality of life, and even death – then, there is still a significant amount of data from that period that shows most of horrific accidents (the majority of which were attributable to human error and resulted in both permanent disabilities and death) occurred during the later hours of the 2nd shift.

In the early 20th century, as manufacturing expanded into transportation, work days were again revised into three shifts – 7 am – 3 pm, 3 pm – 11 pm, and 11 pm to 7 am – with similar higher accident rates in the 2nd and 3rd shifts.

Medical professionals in hospitals, nursing facilities, and emergency services work were the next group of people to be required to work in shifts. Additionally, of all the careers in which shift workers were employed, it was not unusual for many medical professionals to work double shifts (back-to-back shifts) to provide necessary services.

Medical professionals in hospitals, nursing facilities, and emergency services work were the next group of people to be required to work in shifts. Additionally, of all the careers in which shift workers were employed, it was not unusual for many medical professionals to work double shifts (back-to-back shifts) to provide necessary services.

During World War II, almost all manufacturing facilities in the U.S. transitioned to 24/7 production and a 1st, 2nd, and 3rd shift to support the Allies’ efforts in the war. After World War II, as those factories transitioned back to civilian manufacturing, they kept 24/7 production and three shifts in place.

As the Technological Revolution replaced the Industrial Revolution (also in two iterations, with the first one beginning after World War II, and the second one, which now affects every human on the planet, beginning in the late 1960’s) and the world became instantaneously and simultaneously intricately connected, the 24/7 workday began to affect almost everyone on the planet,  including white-collar workers who saw their workdays – and nights – lengthened beginning in the late 1980’s.

including white-collar workers who saw their workdays – and nights – lengthened beginning in the late 1980’s.

As more and more people have been, by necessity, forced into living and working in a 24/7 environment, researchers have kept a close eye on how successful our efforts to work against our natural circadian rhythms have been.

The answer is we’re all pretty much failures at it and the results are poor quality sleep and sleep deprivation.

And like our ancestors in the Industrial Revolution, working late into the night or all night, whether in a medical facility, an emergency services department, a manufacturing facility, an office, or at home (because half the world’s awake when it’s time for people in the U.S. to go to bed), shows the same elevated risks of accidents and injuries (both work-related and non-work-related) when compared to working during daylight hours.

Here are a few statistics directly tied to shift work (if you’re an office jockey reading this, remember that this applies equally to you and all those late nights and overnights you’re working wherever you’re working them):

- Work-related injuries increased to a little over 15% on the 2nd shift and almost 28% on the 3rd shift.

- The longer the shift, the higher the risk of injuries: 13% higher on a 10-hour shift and almost 30% higher on a 12-hour shift.

- The more consecutive night shifts worked, the greater the risk of sustaining an injury (37% higher by the fourth consecutive night shift as opposed to 17% higher by the fourth consecutive day shift).

- Almost 50% of the late-night (10 pm – 1 am) and early-morning (5 am – 8 am) car accidents – fatal and non-fatal – involve drivers who are driving to or from work.

Pretty scary, huh? And, yet, despite all the evidence that it’s a really bad idea, a dangerous idea, and a dumb idea, we, as a society, keep doing it. I won’t get in-depth into the reasons for that here, except to say that they are tied to greed and competitiveness, which are soul issues.

What is the biology behind the statistics above?

That we can answer. And I’ve had more jobs than not where I worked 10-12 hours on a Sunday-Thursday night schedule, where I’ve worked many late, late nights only to be back at my office first thing the next morning, and where I’ve pulled many all-nighters, so I’ve got a lot of firsthand experience to bring to the table.

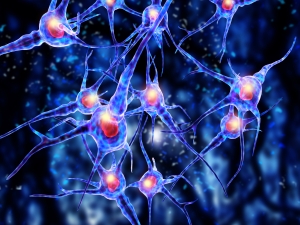

The reality is that unless you’re physically exhausted – mental exhaustion actually keeps the brain in gear and is totally counterproductive – you can’t get any real quality sleep during the day. Melatonin production is off and all the hormones to keep you awake are in action, so trying to sleep well is a losing battle.

So while you may be able to get a few hours of restless sleep, you do not go through the normal sleep cycles associated with nighttime restorative sleep.

As a result, because your brain is “foggy” when you’re awake, your response times are sluggish, and, combined with the normal circadian rhythm of sleep kicking in at night – even if you’re awake – all of these are directly tied to the increased risks of accidents and injuries during work hours at night.

The later you work at night the more likely you will have an injury and/or accident because these are the normal hours when sleep is deepest and during which you’ll be fighting sleep the most.

But the long-term effects of poor sleep and sleep deprivation are just as serious with regard to neurological health.

In a series of studies on sleep published in late 2013, researchers discovered that good sleep and normal sleep (7-8 hours at night) enables the brain to clean out the toxins – including beta amyloid proteins, which are involved in the development and progression of Alzheimer’s Disease – that have accumulated in it during the day’s mental activities. This process is so energy-intensive that it can be done only during sleep, when the brain doesn’t have anything else to do.

And here’s the thing. Perpetually skimping on sleep, for a lot of us who don’t do shift work and don’t have careers that demand a lot of late, late nights and early, early mornings on a consistent basis, is a lifestyle choice.

Technically, however, all of these types of careers, except for manufacturing work, which puts food on the table and pays the bills for people who might not be able to do so otherwise, are lifestyle choices because anyone going into these careers know the demands before they choose the education and jobs that lead to them.

And that substantially increases your risk of developing a lifestyle dementia.

We, as a society, are very sleep-deprived. And that includes a lot of people who are not earning their living during the night.

We, as a society, are very sleep-deprived. And that includes a lot of people who are not earning their living during the night.

Much of that, in my opinion, is because we are digitally and electronically connected all the time and that crowds out the time we allocate for sleep.

A few questions should help you know if this applies to you personally.

- Do you watch TV for several hours in bed or do you play video games before you go to sleep?

- Is your smart phone or tablet beside your bed so you can check email or keep up with social media? Do you check them during the night?

- Are you digitally and electronically connected last thing before you close your eyes at night and first then when you awaken in the morning?

- Do you remember what you did at night before you got digitally and electronically connected?

If the answer to the first three questions is “yes” and the answer to the last question is “no,” then you’re making a lifestyle choice, probably sacrificing sleep (it’s important to remember that all these digital and electronic things stimulate the brain, so their after-effects stay with you for quite some time after you turn them off, and that means it takes you longer to fall asleep), to stay connected all the time to a world, that quite frankly, isn’t all that important or real anyway.

And whatever is real or important about it can wait until tomorrow. Like it did when a lot of us were little kids and there was no cable tv, there was no public internet, there were no video games, there were no personal digital/electronic devices, and there were no cell phones.

The world didn’t end then, and it won’t end now if you put all these away early in the evening and give your brain a chance to relax by playing a game with your family, listening to music that soothes your soul, getting lost in a book, or simply being quiet for a little while, using that time to meditate and reflect on your day and make plans for tomorrow.

Even though since I was born I’ve always had trouble sleeping a lot and getting good sleep when I do, I purposely shut everything down early in the evening to engage in quieter and more reflective activities and I stay away from it until I’ve had some quality time in the morning to get ready to tackle it again.

One day each week – for me, it’s the weekly Sabbath – I disconnect completely for the 24 hours between sunset Friday and sunset Saturday, and I’ve begun to move away from being connected much on Sundays as well.

I rarely have my cell phone anywhere near me and even when I do, I rarely use it. I certainly don’t want it in my bedroom with me at night.

With my sleep history, I’m already behind in this game, so I make lifestyle choices to improve my odds the best I can. It may not be enough to stave off dementias, but at least I know the choices I’m making increase the odds that, if I live long enough (I always pray I don’t…we start dying the day we’re born, so it’s pretty much all downhill from that point on), they’re either mild or short and done.

For all of us who can read this today, now is the time to start making sure we’re doing everything in our power to get enough sleep and to get good sleep when we do. That’s a lifestyle choice that only you can make for you and that only I can make for me.

It may mean some hard choices. It may mean a career change. It may mean disconnecting during nighttime from technology. It may mean looking at our lives and figuring out what’s really important in the long-term, instead of buying into the pervasive idea that now is the only important time in our lives.

But in the end, from this moment on, at least in the realm of sleep, you can do something to help yourself, but you have to decide what you’re willing to trade off now and what you’re willing to live with in the future.

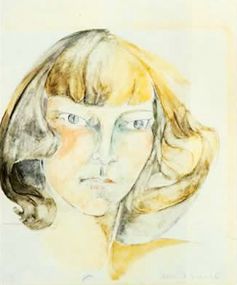

While it is well known now that President Franklin D. Roosevelt suffered from partial paralysis from polio (he was stricken with the disease when he was 39 years old) that was hidden from the United States during his twelve years as president of the country, what is hardly known is that in the last several years of his life, President Roosevelt’s diastolic hypertension grew significantly worse and he began suffering symptoms of vascular dementia as a result.

While it is well known now that President Franklin D. Roosevelt suffered from partial paralysis from polio (he was stricken with the disease when he was 39 years old) that was hidden from the United States during his twelve years as president of the country, what is hardly known is that in the last several years of his life, President Roosevelt’s diastolic hypertension grew significantly worse and he began suffering symptoms of vascular dementia as a result. Many of the factors that should have been addressed with Stalin and the Soviet Union at this conference by President Roosevelt (as the leader of the world’s strongest nation, which the United States emerged as in World War II) were not.

Many of the factors that should have been addressed with Stalin and the Soviet Union at this conference by President Roosevelt (as the leader of the world’s strongest nation, which the United States emerged as in World War II) were not.